Digital data is a core resource for digital humanities, but digitised archival data also needs to be integrated, interoperable and potentially unified with the global network of GLAM (Galleries, Libraries, Archives and Museums) or Europeana’s Linked Data Web service.

In practice: what needs to be done for an Archival Institution to offer its vast data collection as linked (open) data?

While in Stockholm and hosted at the Swedish National Archives (Riksarkivet) during my ongoing ODECO secondment, I have had the chance to experience through hands-on work how a custom data schema describing archival data can be standardised to pave the way towards the linked data paradigm.

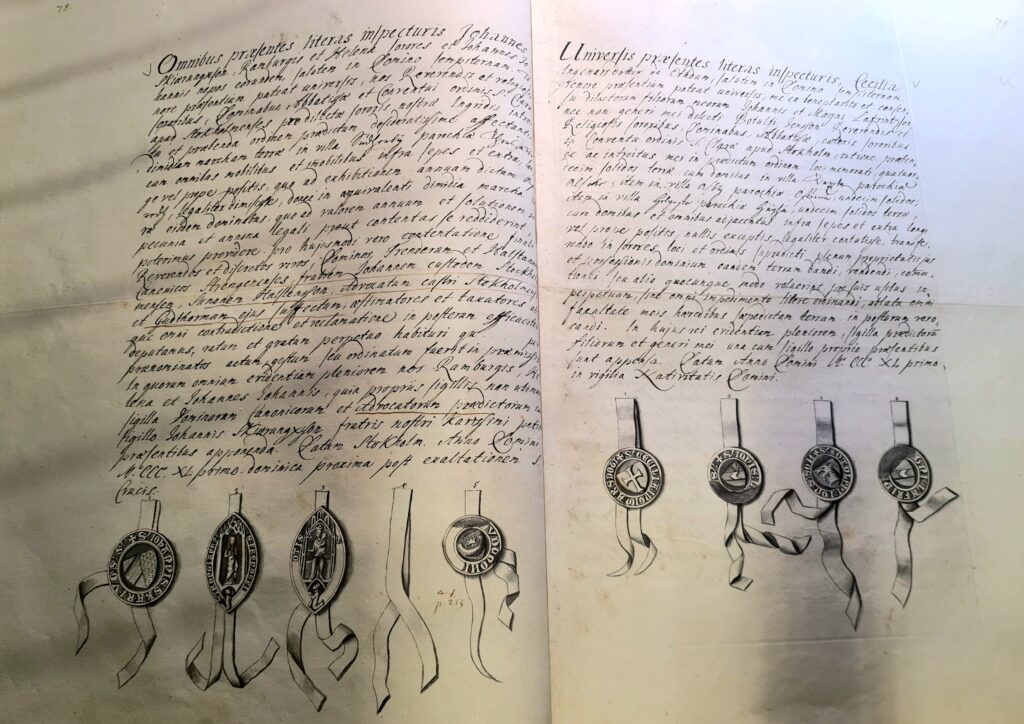

The Swedish National Archives is the authority responsible for preserving Sweden’s historical and cultural heritage- millions of archival records (mounting over 75 km of physical artifacts..), and although digitisation is still ongoing, over 240 million digital artifacts are already available through their search service (söktjänsten).

Impressive fact: the Swedish National Archives facility is partly built inside solid rock providing a protected environment for preserving historical documents, as the rock helps maintain a stable temperature and humidity, crucial for long-term archival storage. The facility was specifically designed to take advantage of the natural insulating properties of glacial erratics (rock formations from the last Ice Age and commonly encountered in Stockholm as well), protecting valuable records from external environmental changes and potential disasters. At first glance the building appears to be only 2-3 floors tall, but hiding over 11 floors underneath (some of them visible if the building is viewed from the sea).

Familiarising with the archival world and structure by looking into exchanged letters between Swedish nobleman Hans Axel von Fersen and Marie Antoinette (a nice reminder of “scripta manent” and that your instant messaging app history might be studied by nosy cyborgs in the -maybe not so distant- future..!), and drawing a taxonomy of the archives as a mental model for intuition, I commenced with the alignment of the local data schema with the Records-in-Contexts Ontology (RiC-O) for archival records description. This process aims to express archival resources as Linked Data (or Archival Linked Data – ALD).

A couple of weeks ago, the first experts’ Workshop session was held to discuss and validate the progress in the conceptual mapping between the local data schema and RiC-O, the former based on the ARKIS (Riksarkivets arkivinformationssystem) information system structure and NAD (Nationell Arkivdatabas) design principles. The group of 7 experts that attended the Workshop consisted of: 2 archivists in the Swedish National Archives, 2 archive technical advisors, 1 business developer who specifically works with archive digital access, 1 systems developer and section manager, and 1 unit manager of archives digitisation and the AI-lab of the Swedish National Archives.

The experts discussion held during the Workshop continued in the weeks after to ensure consensus on the conceptual mapping result and was followed by recommendations regarding the implementation process and documenting the challenging aspects that need to be considered for our case. The conceptual mapping was then visualised using ontology development tools such as Protégé, and formatted appropriately (e.g., .json serialisation) to facilitate eventual implementation in the Linked Data API.

Lessons learned from the Swedish capital may enable replication of this methodological process in other countries’ similar context. Further future experimentation may also show how/if we could integrate semi-automated approaches in the ontology alignment process utilising technological means (e.g., Large Language Models). This is a research territory worthy of investigation considering the potential of knowledge graphs to improve LLMs’ performance on domain- or knowledge-specific tasks, but also vice versa.

Author:

Maria Ioanna Maratsi, University of the Aegean