The state-of-play in the EU

In the European Union, the concept of “high value datasets” has been introduced by way of the Open Data Directive.

- Recital 66 of the Open Data Directive states that certain open government datasets are associated with “important socio-economic benefits”.

- The definition of “high-value datasets in Article 2(10) further elaborates by stating that these datasets are “associated with important benefits for society, the environment and the economy, in particular because of their suitability for the creation of value-added services, applications and new, high-quality and decent jobs, and of the number of potential beneficiaries of the value-added services and applications based on those datasets.”

Based on these attributes, the Open Data Directive requires public bodies to make these datasets available for re-use free of charge (in most cases), available as bulk downloads and accessible through APIs, and machine-readable.

In December 2022, the European Commission passed a regulation specifying different types of high-value datasets from 6 sectors – geospatial, earth observation and environment, meteorological, statistics, companies and company ownership, mobility.

Tim Davies has written about this “strong economic frame” adopted in the definition of high-value datasets. He writes that the benefits of open data cannot always be quantified by adding up the revenue of firms who use open data. Instead, value is realized in other ways too. For instance, he identifies a couple of other ways in which value is realized from open data – fostering risk reduction, increasing internal efficiency and innovation, enabling exercise of rights, realizing value through network effects, redistributing surplus value. As a result, he notes that we need new calculative logics to capture these types of value realisations.

The view from India

In India, the equivalent of the Open Data Directive is an executive policy known as the National Data Sharing and Accessibility Policy, 2012. This policy does not mention high-value datasets.

However, the vocabulary of high-value datasets became introduced into Indian law and policymaking since 2020. For instance, a parliamentary expert committee was set up in 2019 to recommend regulatory frameworks for non-government data. This committee released a report in December, 2020, which introduced the term high-value datasets. BUT, the committee defines high-value datasets as datasets that are “beneficial to the community at large and shared as a public good.” The report provides some illustrations, which ofcourse includes datasets that have the potential to create more jobs or enable more innovations. But the report also identifies datasets that are relevant for citizen engagement, poverty alleviation, financial inclusion, skill development and divert and inclusion as high-value datasets. A later report released by NASSCOM – the National Association of Software and Service Companies in India – echoes a similar broad understanding of high-value datasets.

This illustrates a more balanced approach to high-value datasets in India – one that combines the economic value of open datasets with their social value.

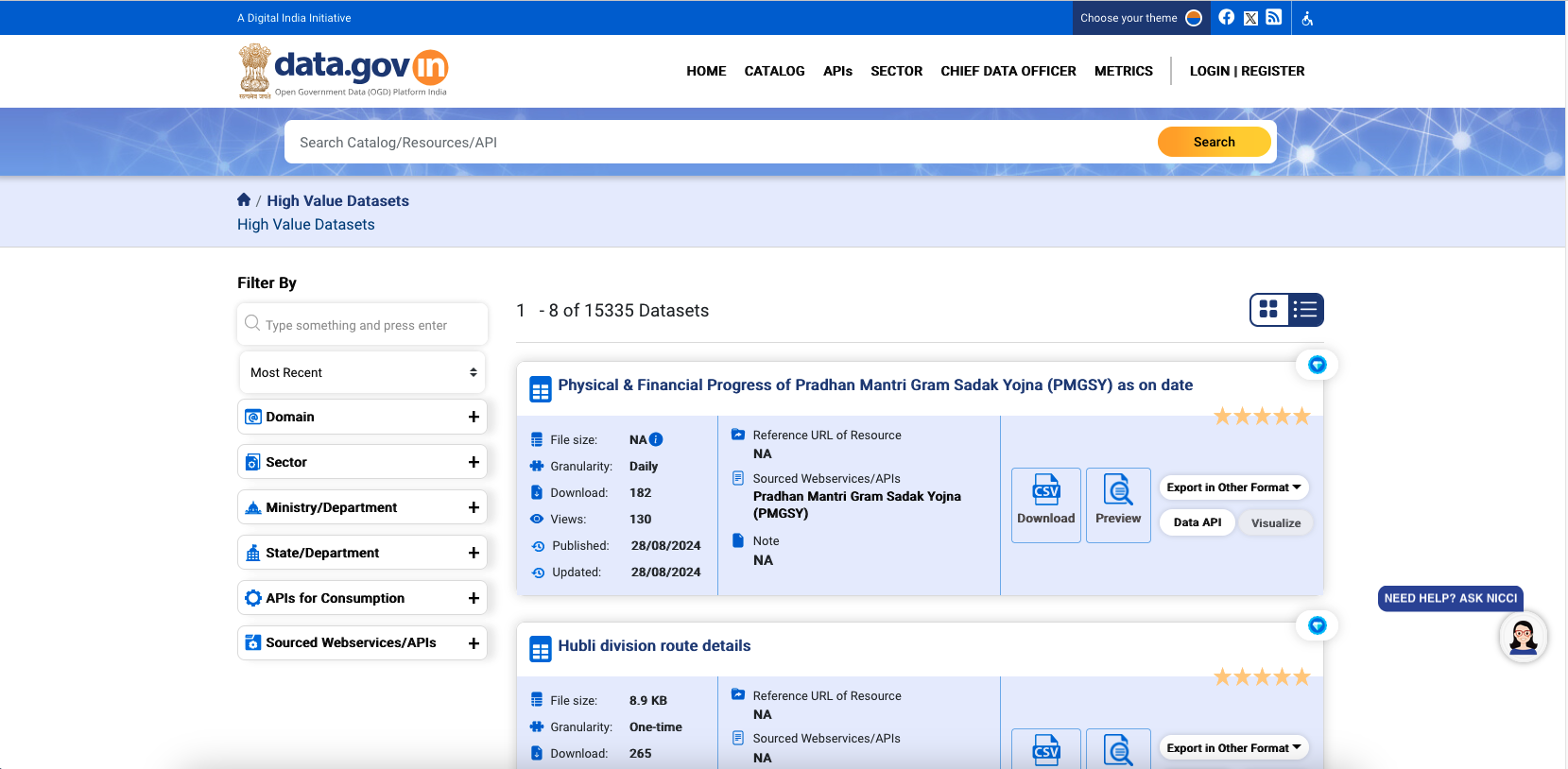

At present, India’s open data portal hosts more than 15000 high-value datasets. Datasets relating to tuberculosis treatment outcomes, expenditure and progress of road construction projects in rural areas, public spending on welfare schemes, and tax revenue of the federal government – to name a few. This illustrates a different more socially-conscious approach to implementing high-value datasets. And in doing so, it offers a knowledge transfer opportunity for EU policymakers.