There have been many recent controversies concerning AI systems, especially what is being termed “general-purpose AI”. These AI systems are trained on vast amounts of unlabeled data and can be used for different tasks, as opposed to one specific task. The most famous example of general-purpose AI is ChatGPT.

(Screenshot of a conversation between me and ChatGPT – highlights are my own)

General-purpose AI like ChatGPT (and others like Gemini or DALL-E) are extremely useful. But given their training needs, they are trained on large amounts of publicly-available data. This includes openly licensed content, which is creating new challenges for copyright.

In most jurisdictions, creative works like books, photographs, paintings are subject to copyright. Copyright is a proprietary claim held by the artist of these creative works, to prevent copying or extraction of her creative labour.

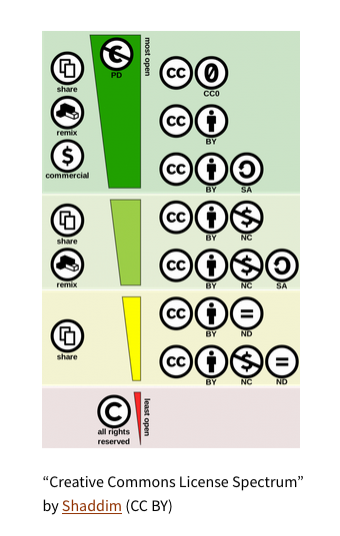

In the early 2000s, many proponents of the ‘open culture’ movement, sought to create legal tools to allow more sharing and re-use of creative works in an effort to create a “remix” culture. This led to the birth of Creative Commons licenses. These are legal instruments by which artists could provide pre-facto authorisations for the use of their copyrighted works. The innovation of Creative Commons lies in its modular components – allowing artists to choose the extent of ‘openness’ they want to provide to their creative works. An artist can waive all copyright claims by using the public domain declaration (i.e the most open license). Or an artist can require that downstream re-users either attribute them, share derivative works on similar terms, or create derivatives only for non-commercial uses.

With the rise of general-purpose AI, the project of Creative Commons needs to grapple with new risks. Artists who release creative works under CC-BY (requiring attribution for downstream use) licenses are concerned that their works are used to train AI systems like DALL-E, which produces eerily-similar artworks as their own but does not attribute them. Other researchers raised ethical issues – such as the use of openly licensed images hosted on Flickr being used to train facial recognition AI technologies.

General purpose AI like ChatGPT and DALL-E need vast amounts of data to meet their training needs. In this regard, openly licensed content is crucial to the development of these general purpose AI systems. But the terms of the open license used by artists are not respected by the AI developers. Simply because openly licensed content is available on the Internet, AI developers scrape and use it for training AI systems without paying attention to the license terms embedded within these images.

This calls into question the role of licenses like Creative Commons in the AI age. Creative Commons itself recognized the importance of this question, in their 2021-2025 strategy:

How do we craft open data licenses to ensure more openness, but also addresses artists’ concerns of extractivism? Further, since open licenses are subject to voluntary adoption by artists, how can we ensure artists are not chilled from releasing their future works under CC licenses?

Perhaps part of the answer lies in supplementing open data licenses with other legal frameworks for transparency. Article 53 of the new AI Act for the European Union marks a step forward in this regard. Article 53(1)(d) of this law states that AI developers must “draw up and make publicly available a sufficiently detailed summary about the content used for training of the general-purpose AI model, according to a template provided by the AI Office.” These kinds of transparency obligations can allow artists to hold AI developers like OpenAI accountable for re-use of the artists’ creative works.

While the hype around AI takes focus away from the people and political choices underpinning AI, it is also important to design legal frameworks that account for unique risks and harms of AI. The European Union has taken the first step with legal frameworks like the AI Act. It remains to be seen how effective this will be in sustaining the culture of open sharing and open data.