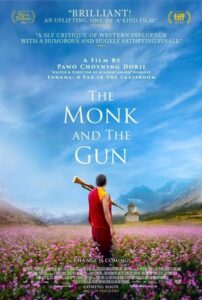

One of the privileges of conducting research in social sciences is finding inspiration in everyday life. Last week, I watched The Monk and the Gun, a gem of a film that I highly recommend. But there’s more to it. Without spoiling the movie, it offers profound insights into the concept of traditional knowledge and how state views tend to categorize us into rigid data boxes. “Why would they need our birth dates?” asks a rural inhabitant about to register for the mock elections in Bhutan in 2007. While we often take for granted the need to express knowledge in numerical values, such as birth dates, it’s worth questioning whether all data we collect is meaningful in the way we’re accustomed to.

A key reference on this topic is James Scott’s book Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (1998). Scott reflects on the high modernism ideology behind data collection practices. Have you ever considered that census data might not truly capture important information about you? What exactly is a family, a forest, or even an environment in the eyes of the state? Do these data points serve to control us, or do they genuinely improve our lives? In a reflection from Gulşen Güler’s keynote at the Critical Data Studies workshop (more on the workshop here): How do we define a household? How do we use information about households? Are we, consciously or not, categorizing households as “good” or “bad” based on arbitrary criteria like square meters per child?

The Monk and the Gun illustrates how the needs of local and rural populations can differ from the state’s inherent drive for conformity. This ties closely to open data, as much of the data governments make public are collected in ways that prioritize uniformity over individuality.

So, What Are Possible Solutions?

- Integrating Traditional Knowledge with Census Data: Traditional knowledge offers invaluable insights that can complement formal census data. For example, indigenous practices in land management, community organization, or resource allocation often reflect deep, context-specific wisdom that standard data collection methods might overlook. By integrating this knowledge with official data, we can create a richer, more nuanced understanding of communities that goes beyond mere numbers.

- Adopting a Bottom-Up Approach: Instead of relying solely on top-down methods of data collection and policy-making, we should shift our focus to a bottom-up approach. This means valuing the perspectives and needs of local communities, particularly those often marginalized or underrepresented. Policies and decisions informed by grassroots data are likely to be more inclusive and effective, addressing the real needs of the people rather than imposing generalized solutions.

- Empowering Individuals as Data Creators, Not Just Data Subjects: We often see ourselves as mere data points within vast systems, but it’s crucial to recognize our power as data creators. By actively participating in the data creation process—whether through citizen science, participatory mapping, or local surveys—we can ensure that the data collected is more representative and relevant. This shift from being passive data subjects to active data creators allows communities to tell their own stories and assert their unique identities in the face of homogenizing state narratives.

Author

Caterina Santoro, KU Leuven, Belgium